Liver Cancer: A Primer

With October being recognized as Liver Cancer Awareness Month, the National Foundation for Cancer Research (NFCR) presents to you a quick overview of the disease—and too insight into the importance of early detection and recent advances to that end.

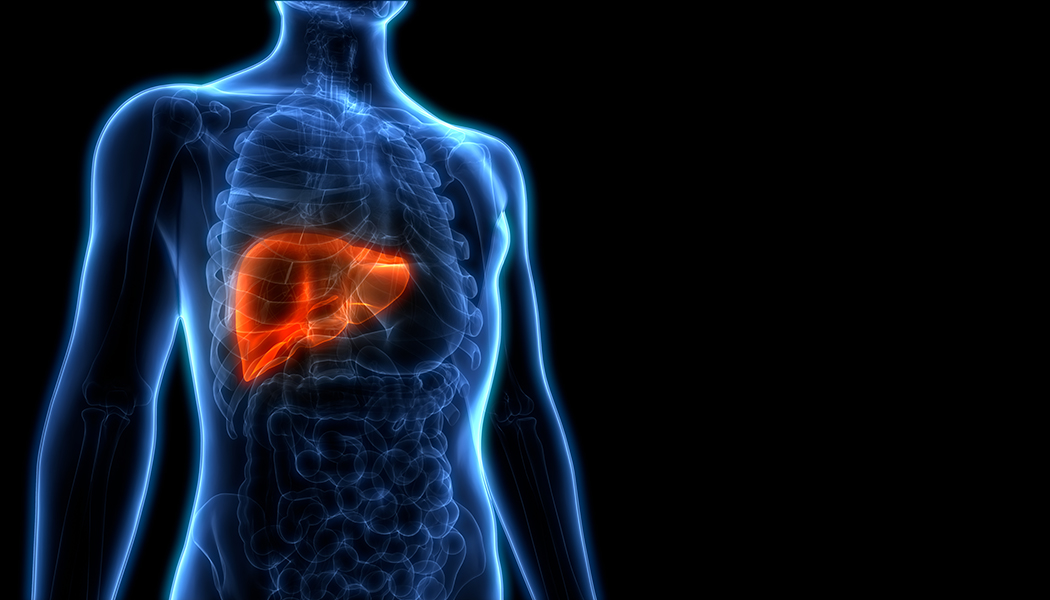

According to a July 2018 report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, deaths from liver cancer soared 43% in the years spanning 2000 to 2016. With the exceptions of ethnic Asians and Pacific Islanders, increased mortality rose for all groups across racial and gender lines. This spike actually pushed the disease to the sixth leading cause of cancer death in 2016, whereas it had been ninth at the turn of the millennium.

“And unfortunately, the symptoms are nothing—patients usually have none at all to start,” says Dr. Talal Adhami, a member of the American Liver Foundation’s National Medical Advisory Committee, highlighting why this particular cancer is so notoriously hard to recognize. “That’s why they have to go on a surveillance protocol with an ultrasound every six months.”

By the time symptoms do present themselves—often in the forms of abdominal pain, fatigue, jaundice, liver failure and/or swelling around the belly—it is a dire sign that the cancer has progressed into its advanced stages. But it is also not unusual for even advanced liver cancer to present no symptoms. Adhami admits that when liver cancer is finally diagnosed, most often the prospects for a cure are already dim. But that is not to say science is completely in the dark.

While liver cancer itself can fly under the radar, only very rarely does it spontaneously occur. Adhami stresses that any sort of liver scarring, no matter the cause, increases risk. Smoking and obesity are two conditions also known to contribute to liver cancer, and even poisoning via some molds and mushrooms.

However, liver cancer most often precipitates out of standing liver conditions whose symptoms are far more easily recognized. In the case of hepatocellular carcinoma, the most common type of primary liver cancer, people with chronic liver diseases, such as cirrhosis caused by hepatitis B or hepatitis C infections, are considered most at risk. Both present symptoms that are difficult to go unnoticed, such as dark urine, vomiting, itchy skin, abdominal swelling and swelling of the legs. Alcoholism is also, perhaps famously so, a cause of cirrhosis. Alcoholic hepatitis presents symptoms including jaundice and also vomiting. It is due to the high-risk factors of these diseases that patients are put under surveillance.

Unfortunately, each of these conditions themselves are very gradual in their development. Indeed, Dr. Jiaquan Xu, the author of the CDC report, suggests the present rise in liver cancer deaths may stem all the way back to before 1992, the year it became mandatory for blood transfusions and organ transplants to be screened for hepatitis C, whose progress is extremely slow. The CDC lists both procedures as a one-time most common means of hepatitis C transmissions. Adhami adds that hepatitis B infection, also slow-acting, now most often occurs during pregnancy from mother to child.

“But if you bring hepatitis B under control,” he goes on to say, “you have the opportunity to reduce the chances of hepatocellular carcinoma. And it’s the same thing with hep C.”

However, if cancer is found, treatment then depends on its stage and tumor size.

“If the patient has good liver function, not a lot of scar tissue and the cancer is a small mass, then a resection surgery of the cancer can be curative and has a very good five-year survival rate,” says Adhami. “But if the liver is failing, yet the cancer is identified early and there are three tumors or less under an inch-and-a-quarter in size, a liver transplant is the best option.”

But even at more advanced stages, recent advances can give liver cancer patients hope. If a patient has a single, large tumor, Adhami describes the process of embolism, where surgeons cut off the blood flow to the mass and essentially starve it to death. Another process involves injecting beads either irradiated or coated with chemotherapy into the tumor, thereby killing it or shrinking it to the point that transplantation becomes a viable option. Kinase inhibitor drugs also show promise and are an approved treatment in select groups.

Despite these new venues, the old logic still holds true: Adhami affirms that early detection is the best “cure.”

“The good thing about screening is that when and if the cancer is caught early, it is actually curable,” he says. “Not only treatable, but curable.”

Advance in such early detections are underway. A team led by Jim Basilion, Ph.D., an NFCR fellow at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, has developed an imaging probe that is able to detect even the tiniest amounts of cancer-related molecules, allowing for early detection. One such molecule, PMSA, can be found in the vasculature of liver tumors which, until now, have never been identified before it is too late and the cancers are beyond treatment.

References:

- NFCR thanks Dr. Adhami for his Fall 2018 interview

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db314.htm

- http://fortune.com/2018/07/17/liver-cancer-death-rate-increased/